Becoming a Place of Belonging

/Written by Heidi Shin, Published by Barr Foundation

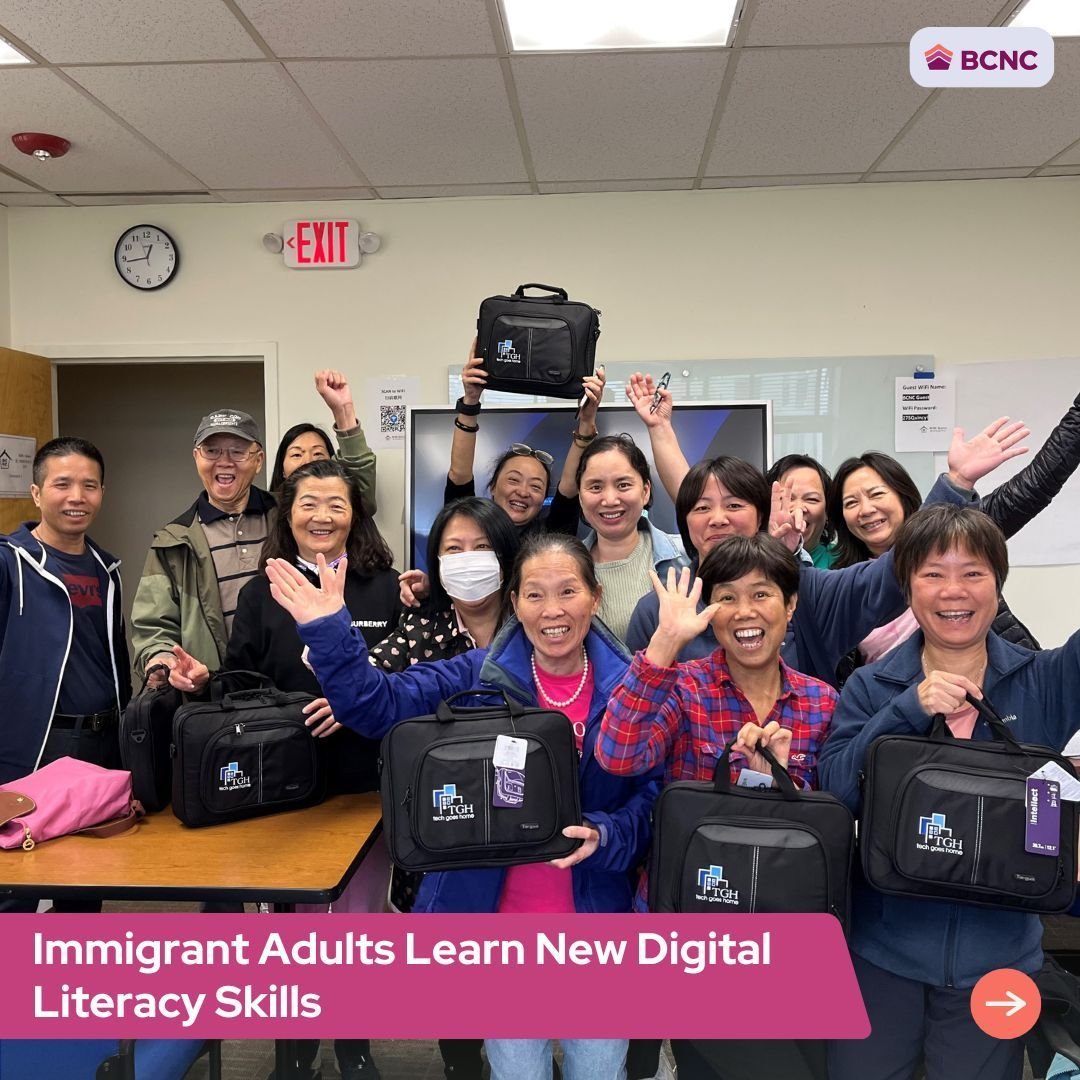

Staff from Boston Chinatown Neighborhood Center (BCNC) share reflections on implementing an internal diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging process.

Ben Hires was just settling into his role as the new CEO of Boston Chinatown Neighborhood Center (BCNC) when the news hit in 2020 – George Floyd had just been killed by police.

Hires knew they needed to respond. While BCNC had been an organization that always valued racial justice, now the needs had become more urgent.

As a community organization, BCNC runs Pao Arts Center, a community-based arts and culture center, and it also operates an early education child care, afterschool programs, and support services for recent immigrants, such as counseling, English language classes, job training, and more.

He recalls “Even though we’re an organization that serves Asians and other communities of color, racial justice and equity was a topic that we could still use help in.”

And so birthed the nonprofit’s DEIB Process – a deliberate and ongoing cycle of listening and responding to staff concerns and needs around issues of diversity and equity. Note they added the letter “B”, to the well-worn acronym “DEI” (standing for diversity, equity, and inclusion) to emphasize a sense of belonging.

The DEIB Process continues the work of staff trainings and a BCNC staff-led cultural competency group, which formed in May 2020, and whose efforts laid the foundation for this current work.

“Even though we’re an organization that serves Asians and other communities of color, racial justice and equity was a topic that we could still use help in.”

The day I visit the Pao Arts Center, Artist Wen-Ti Tsen is overseeing the installation of an exhibit featuring his work: they’re exquisite clay models of immigrant laborers in Chinatown, which will be cast into bronze and permanently installed in the neighborhood.

Photos by Heidi Chin - Artist Wen-Ti Tsen oversees the installation of his exhibit featuring sculptures of Chinatown’s immigrant laborers, who faced limited economic opportunities and racial trauma, when they first settled in the US.

In the adjoining room, BCNC staff screen a film about the survival of urban ethnic neighborhoods in the US. It’s part of an all-staff training for BCNC’s DEIB Process, whose goal is to re-shape the non-profit’s culture (whose staff already value diversity ) to be even more inclusive. It isn’t a “one-off” public statement about equity; rather it’s a deliberate and ongoing process of gathering feedback and implementing change, over the course of years.

“The design process has not been as simple as investigating and concluding one way to proceed,” Ashley Yung, Theater and Performance Manager at BCNC shared. “This process is only beginning, and I think there will be more to grow and learn as the process goes on.”

BCNC worked closely with consultant Maanav Thakore from the organization Just Process to devise the following plan:

Build a Design Team with internal staff who are committed to helping the organization become more inclusive over time. Pay staff for their work on this initiative and ensure that diverse staff perspectives are represented on the team.

Design Team conducts focus groups with the organization's staff to learn about DEIB concerns and issues. Ensure anonymity and language access.

Design Team hosts training and workshops in collaboration with consultants to address identified needs.

Design Team reconvenes, to see what’s working…and not working, and to repeat the process of identifying more needs and strategizing how to address them.

It’s been 10 months since BCNC identified their DEI consultant and applied for funding for this project. Since then BCNC has assembled its Design Team, conducted focus groups, and hosted its first all-staff workshop. The Design Team will reconvene in the near future to discuss their findings and to start another cycle of identifying needs.

Below are some of the lessons learned from the BCNC equity design process:

Assemble a Design Team that’s diverse (in race, gender, salary/wage, tenure, and more)

The first step was assembling a Design Team: a group of internal staff who would meet regularly to identify and address DEIB needs. One of the priorities was to ensure that all perspectives from the staff were represented on this team. This meant including senior staff and junior staff, administrators and frontline staff, and people of different salaries/wages, tenure, countries of origin, languages spoken, race, and roles.

But there were inherent challenges; for example, direct service child care providers (who taught children in classrooms from 7:30am-5:30pm) couldn’t participate in a three- hour meeting during the workday. Also how could they accommodate non-English speakers and non-Chinese speakers in the same meetings?

The Design Team was assembled deliberately to represent this diversity. Team members were also compensated for their time spent on the committee.

Hires noted: “In this initial startup phase, compensation is important, because this DEIB work is not currently part of anyone's job description. I think one of the big things moving forward is that this type of work – the planning and execution of DEIB strategies – does become a part of people’s job description.”

In sum, BCNC offers the following suggestions for assembling a DEIB design team:

Be sure that the Design Team represents diverse staff perspectives: Senior and junior staff, administrators, frontline workers, salaried and hourly wage, differences in tenure, language spoken, race, etc.

Compensate staff additionally and fairly for time spent on DEIB activities

Re-write job descriptions to include DEIB work in staff roles

Construct focus groups so staff can speak openly

Next, the Design Team conducted focus groups with the BCNC staff, where in small language-specific groups, they listened to the concerns that individuals faced around equity and inclusion in the organization.

They took the following into account, when conducting DEIB focus groups:

Since staff spoke different languages, all focus groups and trainings were bilingual

Doodle polls were used to identify times when all staff could attend, working around direct service staff’s programmatic responsibilities.

Compensated staff for their time through stipends or paid time off, and as an organization secured additional funding for this. Allocated money to cover staffing for anyone who would need a substitute in their roles, while they attended staff training.

All DEIB concerns could be reported anonymously. Focus groups did not include senior staff and notes taken during focus groups and training were unattributed. All online surveys were also conducted anonymously.

Photo by Heidi Shin - BCNC staff share their thoughts at the first all-staff DEIB workshop

Lastly, to ensure that staff could speak honestly without consequences, the nonprofit hired external consultants/trainers to lead the overall DEIB process. Also note that while CEO Hires is a member of the DEIB Design Team, he and other senior staff are not present at focus groups, so that diversity concerns and issues could be reported freely.

The nonprofit’s DEIB Design Team has met monthly since its inception to guide these processes.

In addition, during this phase, Just Process consultants audited the nonprofit’s history, culture, practices, and policies. They reviewed past staff surveys, organizational human resources documents, exit interviews, and other materials to identify any issues around race and equity.

In focus groups, ask what are you experiencing, and where can we improve?

In the meantime, focus group leaders asked staff this question: “What are you experiencing, where can we improve?” And this is what they heard:

Ashley Yung, Theater and Arts Manager of Pao Arts Center, points out that Chinese Americans born in the US might have different cultural perspectives from recent Chinese immigrants. As a Chinese American, she didn’t know it was disrespectful to refer to parents in their program by their first names; culturally they preferred to be called “so-and-so’s” mother or father.

Yung also acknowledged: “There’s anti-blackness in the Asian community, and I noticed that participants were uncomfortable talking about that. You really have to be vulnerable.”

While the majority of staff and families served by BCNC are Asian American, some are not, especially with the influx of new immigrants to the area, from other parts of the world.

Photo by Heidi Shin: Ashley Yung and Harriet Robinson, two staff members at the DEIB training.

Harriet Robinson, a BCNC preschool teacher who identifies as Black, says that in the classroom, there have been times when children have not wanted to hold her hand. She recalls one parent’s apology: “I'm just so sorry,” she said, “but we've never really seen Black people.”

As younger Black staff have joined the teaching team, Ms. Harriet has become a mentor to them, helping to navigate situations like these.

Adult English language teacher Katie Hamel recounts an incident when a Haitian student was teased about her hair in class, and she responded with a lesson the following week on “how to talk about differences in a more respectful way.”

From the initial Design Team meetings to the focus group, CEO Hires began to see both needs and opportunities for improvement.

From the initial Design Team meetings to the focus group, CEO Hires began to see both needs and opportunities for improvement.

“Staff have not always felt heard or recognized here. It could be a more inclusive space.”

He is adamant about this: “No one here at BCNC should feel like they don’t belong.”

By demonstrating vulnerability in his own leadership, Hires has helped to establish a culture of openness, where his staff can do the same.

His transparency in sharing about how hard this work can be has undoubtedly contributed to the success of their DEIB efforts.

Diversity means different things, to different generations

Hires also sees that diversity might be defined differently by staff, depending on their generation and cultural experiences. For example, younger staff included gender identity in diversity.

Yung shares about the experiences of staff members in BCNC’s after school program who identify as non-binary: “Kids having their own biases might use the wrong pronouns, and finding an age appropriate way of explaining that diversity is really difficult.”

She adds that there’s a learning curve for staff of different generations: “There might be slip ups sometimes, since they’re always learning, and (those who slip up with the wrong pronouns) appreciate when others are patient.”

“Quite frankly, no one is absent of any prejudice or bias, conscious or unconscious,” Ben Hires added. “How do older staff, younger staff, immigrant staff, Asian American staff, how do we all as an organization have a shared understanding, a shared culture, and shared values around diversity?”

Language matters, so does learning style

For some, Hires said, it’s easier to grasp the academic language around diversity work, including terms like ally, bias, decolonization, or intersectionality. It’s important to help all staff to understand these terms, to have a shared language and starting point.

But he recognizes that others, particularly those of older generations and more recent immigration histories, may be less familiar with this terminology and have other ways of learning and engaging in equity work.

It’s important to accommodate different learning styles and experiences of staff, Hires noted. In fact, some DEIB terms may not have direct translations in non-English languages, such as Chinese, he says.

Hires asks: “With older and younger staff, how do we help build a shared understanding of culture and values in an organization in 2023?”

Photo by Heidi Shin - Pao Arts Center staff installing an exhibit featuring the work of AAPI illustrators and graphic designers about the rise of anti-Asian discrimination and violence.

Customize DEIB training to each department, keep things in person

When the first all staff training launched it included three components: 1) Building a shared understanding of equity terms, and reviewing concepts such as systemic and institutional racism, 2) Watching a segment of the documentary film, “A Tale of Three Chinatowns,” which was in effort to build a better understanding of the history of Boston’s Chinatown, and 3) Small group discussions to respond to the film and brainstorm future DEIB ideas for the organization.

The workshop design was collaborative in terms of the agenda and components. The first part of grounding the group in terminology was primarily the work of the consultant from Just Process, while the film screening was led by BCNC staff.

In future training modules, BCNC will continue to respond to issues and concerns they heard about in their focus groups. For example, they are developing a workshop to help staff respond to the racial microaggressions they heard about during focus groups.

Lastly, the initial timeline for their DEIB process proved ambitious, with a COVID and flu-filled winter, resulting in staffing shortages, and other job priorities often taking a front seat.

Hires recalls: “We had an original timeline (where they’d hoped to host the focus group and workshops sooner). But all the work just took much longer, which again, was surprising, but not surprising.”

In the future, to accommodate staff schedules for upcoming workshops, rather than requiring all staff to attend at the same time on the same day, BCNC plans to hold multiple sessions on different days. Hires also emphasized that in-person discussions were better than virtual ones for this type of complex and nuanced work.

Next Steps: Change Policies and Culture. DEIB is an ongoing process, not a one-off workshop

As for next steps, BCNC plans to create new policies and revamp existing ones, to support staff around emerging DEIB issues at work, such as people who are experiencing microaggressions in the office or the classroom. They will also work to create job listings with language that helps to attract diverse staff. BCNC is asking the question: What do hiring processes look and sound like? What biases are there?

At the same time, Hires recognizes that policies alone cannot change culture. The Design Team at BCNC will continue to meet monthly to lead this change, he says, as it must become a process that doesn’t rely on a consultant to be onsite.

Staff will also come and go, Hires noted. How will those who join the organization in the future understand its culture of inclusion and belonging? How can we be a place where everyone feels safe and included, over time, as the organization and its people evolve?

“We’re trying to build muscles within the organization to carry on this DEIB work, not as a one-off policy, but as a dynamic and ongoing process.”

Hires continues: “You never know when there will be the next situation or racial trauma to respond to. So ideally, the more we’re strengthening those muscles to deal with these situations the better.”